In a letter from Vienna to her confidant Roland Penrose, Lee Miller writes, “There no longer seems to be any urgency and also I’m puzzled and grieved by all the goings on …were too kind to the enemy…but since the allied high command has declared that Austrians are liberated instead of conquered, I’m having to work on that principle.”

After reporting on World War II for the British and American Vogue from mid-March until May 1945 in Germany, Lee Miller (1907-1977) arrived in Vienna in August. Like most cities of the Drittes Reich, Vienna’s sights resembled piles of rubble in front of her. Taking photographs of ruined buildings was not new to her, but was new to others – including the soldiers of the allies – around her.

In another personal letter to her partner, LM writes in rage that she got used to justifying her task as a war photographer to the people, who told her that photographing such scenes would not make interesting pictures, since the local monuments had been ruined. But she kept insisting on her task, “The first ten times I explain that I’m busy making documents and not art.”

A selection of Lee Miller’s underexposed photographs of the immediate post-war period of Vienna was recently exhibited at the Albertina in Vienna, as part of a retrospective on her contribution to the Surrealist movement in Paris and to war journalism. The exhibition, curated by Walter Moser, traced several phases in LM’s life. It started off with her well-known work with Man Ray, focusing on the technique of solarisation, and closed with her photographs of Vienna, which marked the end of her career as a war reporter. Important parts of the show were her displayed photo-essays from Germany for Vogue Magazine. As they were embedded within a different context, the nature of her commentary photojournalism was changed to that of archival documents – appearing out of vogue. At the museum, LM’s war reports become more approachable to a wider public and open for individual reflexion.

This was the first time that LM’s photography was exhibited in Austria, and her son Anthony Penrose visited the Albertina to give a moving lecture on the life of his adventurous mother.

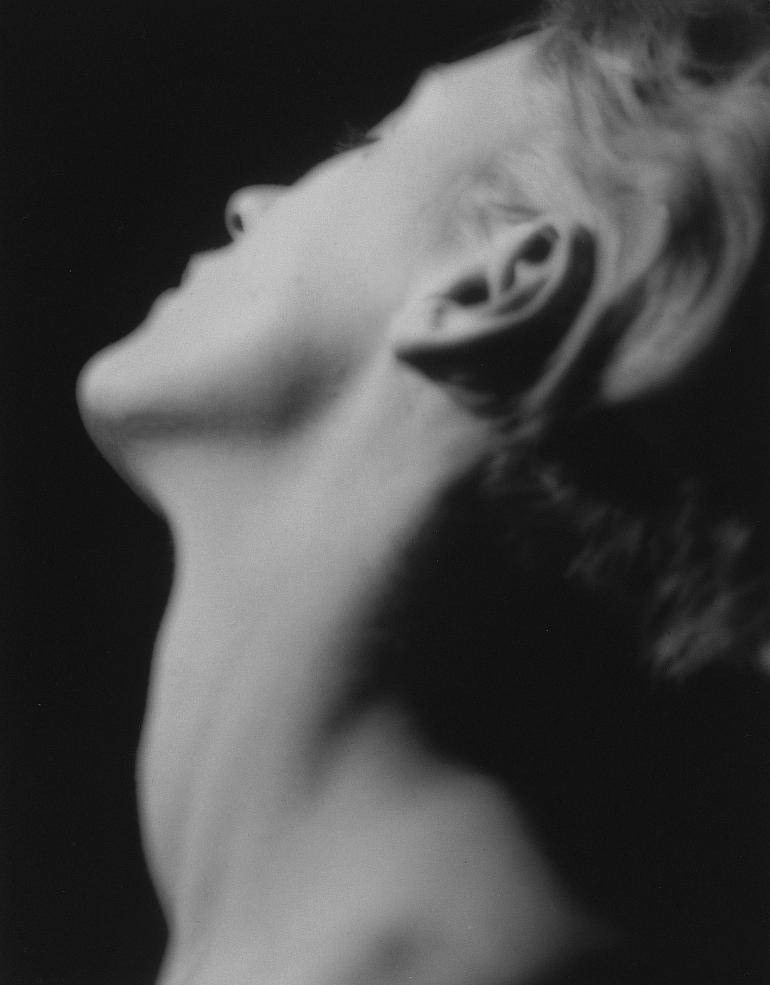

The opening image of the exhibition shows Man Ray’s black and white photography of LM’s neck, which is completely exposed towards the camera’s lens. The positioning of her neck and its implied gesture create a visual embodiment of Lee’s fragility and vulnerability. This picture of her is only half-faced, as she shuns away from any eye contact with her passionate adorer and teacher in this particular instant. But even without seeing her full face, her role as Man’s muse and photo model becomes evident. In the first room of the exhibition, her neck is exhibited twice: the picture whose authorship is attributed to Man Ray is clear, while the juxtaposed photo, attributed to Lee and Man, is out of focus.

Several years later at wartime, LM – who was used to developing her pictures by herself – sent her work to the London offices without having seen it with her own surrealist-trained eyes. As she did not travel with a portable darkroom, she could not develop her pictures. Left in uncertainty about the quality and acceptance of her photographs and texts – LM had not written for print publications before – her work relied on her responsiveness to the situations she found herself in during wartime on the European continent. Yet, both her activities as a writer and photographer appear to a great extent intentional. It appears as if her photojournalistic work changed her approach to photography, as it has a different aesthetic quality to her pervious pictures. Neither do her war images echo solely her subjective impressions, nor do they show fragmented details, but, they give birth to another subjectively based approach towards her picture-making: the pursuit of a documentary intention.

LM’s physical presence in the moment, or rather at the end, of the ongoing war resulted in her lifelong stuggle with digesting her commitment to the war reporting she provided to a female Anglo-Saxon readership. Vogue’s war reportages, an Art of photo-essays, were made up of LM’s texts and pictures, and provided the readers with a textual-imagery made directly at grounds of war. In her texts on her travel through Germany in 1945, she writes, “Germany is a beautiful landscape dotted with jewel-like villages, blotched with ruined cities, and inhabited by schizophrenics… Mothers sew and sweep and bake, and farmers plough and harrow; all just like real people. But they aren’t. They are the enemy. This is Germany and it is spring.” This makes clear that LM was well aware of her role as an American war reporter. She had a clear political stance; she created an image of the people in Nazi-Germany for the Anglo-Saxons.

Lee Miller captured the gruesome events – she first saw with her naked eyes – with her camera, and processed these impressions in her textual work. Yet, as a war correspondent, she was not actively involved in the goings on of war and did not have any time for critical (self) reflection on the work as she had to dispatch it work back to London as fast as possible. The writer Susan Sontag (1933-2004) notes rightly in her theoretical account on the nature of photography In Plato’s Cave that a photographer cannot intervene since s/he records. And a person who intervenes, cannot record the ongoing – as the act of photographing is an event in itself.[1]

Interestingly, both of the above-mentioned commentators, experienced a change in thinking about photography when they encountered the German concentration camps of WWII. As a reporter, Lee Miller saw them with her own eyes. According to the own writings of Susan Sontag, she encountered them in a bookstore in Santa Monica in July 1945 at the age of twelve. She even argues the event of looking at these images for the first time in her life, has divided her life into two parts: everything that happened before she saw the cruel visual documents, and the period, when she started to understand what they showed. “When I looked at those photographs, something broke. Some limit had been reached, and not only that of horror; I felt irrevocably grieved, wounded, but a part of my feelings started to tighten; something went dead; something is still crying.”[2]

LM’s photographs taken at the liberated concentration camps, such Buchenwald and Dachau, can be regarded as an active attempt to create a visual idea of the physical struggle and fatal pain of imprisoned humans in Germany. At the same time, they also shed partial light on her own understanding of the excesses of German Totalitarianism. At the camps, she photographed skeletal corpses, which were amassed to piles, as well as of alive prisoners, who posed next to them. After having climbed inside an open standing rail truck at the city of Dachau, she placed herself in physical closeness to the dead prisoners inside to get a picture. One might wonder, do these photographs of atrocity incorporate an aesthetic distance? Why were none of her pictures taken in Dachau 30 April 1945 – the day Hitler committed suicide and the day after the concentration camp was liberated – published?

The next day, LM and her photographer companion David Scherman left Dachau with the Divisions of the American Infantry. The next stop of the race through Nazi-Germany was Munich, followed by Rosenheim, Salzburg, and the final one was the previous capital of Austria: Vienna.

Austria, which became part of Hitlers Reich in mid-March of 1938, was commonly considered to be liberated after the Red army had conquered it in April 1945.This can be contrasted with the rest of Germany, which is more generally considered to have been conquered at that time. But for LM, it did not make a difference whether she reported from Germany or Austria. For her, both were Hitler’s Reich. After the war had officially come to an end, she took pictures of the prestigious Schloss Belevedere in Vienna, which today presents the greatest collection of Austrian art, and inside the Academy of Fine Arts at Schiller Platz during her one-month stay in Vienna. At the academy, her ingrained surrealist eye reappeared in her photographs of statues. But this time, she decided not take on the role of an exemplary ancient statue – as she did for her task in Jean Cocteau’s film Le Sang d’un Poète (1930). Instead, she played with light and shadow and captured them with her camera. In this exhibited picture by her, the folds of the drapery and the contours of the female statues’ faces seem to be alive.

But despite the rediscovery of herself as an artist in Vienna, she held on to the opinion that Austria had been conquered like Germany, and not liberated. “In a city suffering the psychic depression of the conquered and starving, the Viennese have kept their charming duality, Gemütlich as ever, they are drunk on music, light frothy music for empty stomachs.“ Following from Lee Miller’s observations as a passerby in 1945, Vienna still capitalises on its own cultural heritage seventy years later. Its twenty-century war history, however, has remained an underexposed story.

The Lee Miller exhibition at the Vienna Albertina provided a space for the visual evidence of Austria’s denouement of WWII for thousands of museum visitors (5 May – 16 August 2015). This content is currently on its way to the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale in Florida. Another show of Lee Miller’s work A Woman’s War is going to be on display at the Imperial War Museum in London from October.